Transcript: Introduction

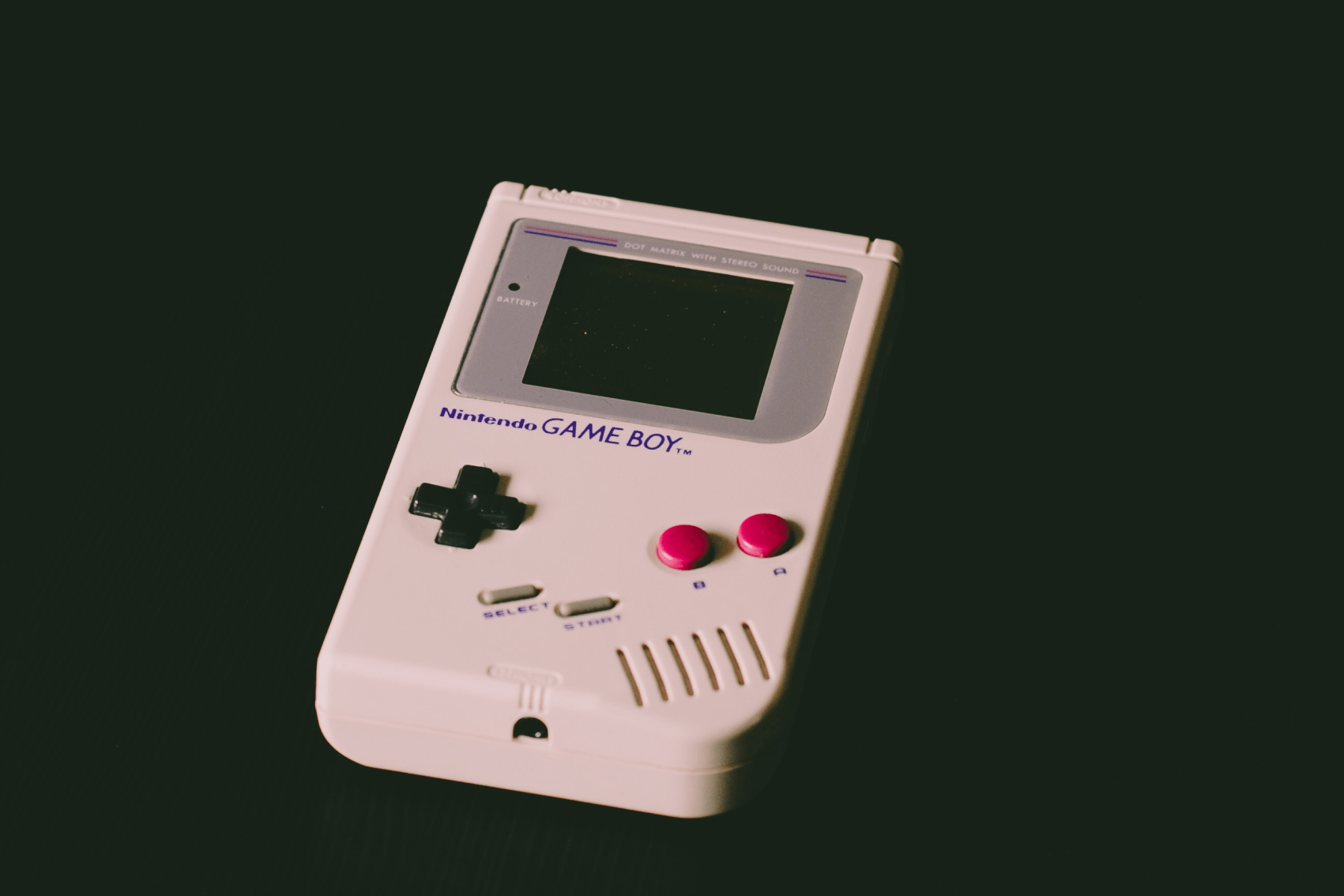

KOSTA: Hello, everyone. Welcome to Undesign. I’m your host, Kosta Lucas. Thank you so much for joining me on this mammoth task to untangle the world’s wicked problems and redesign new futures. I know firsthand that we all have so much we can bring to these big challenges. Listen in and see where you fit in, as we undesigned the topic of online gaming and extremism, from neo-Nazis and far right groups to Islamic state, those seeking to instigate hate and violence for their ideological ends, finding new platforms to do so. As traditional social media platforms crack down on their content, new platforms like the chat application, Discord, live streaming sites like Twitch, online games like Fortnite, and gaming platforms like Steam are rife with extremist content and recruiters. Games themselves are not the problem, but socialization inside gaming related spaces reveals real and pressing difficulties.

Skewed by this reality is also the fact that gaming has been proven to be a source of resilience for many, reaching an all time high during the pandemic, according to polling agency Nielsen, with 82% of global consumers playing video games and watching video gaming content during lockdowns. What is the real picture of the video gaming environment and how do we harness the power and the opportunities present for a greater good, whilst protecting people against the risks that also exist?

Helping us untangle this wicked problem is our latest special guest, Dr. Galen Lamphere-Englund. Galen is a senior researcher and innovation leader in violent conflict, humanitarian and digital rights issues, who currently serves as the Research and Insights Director with Love Frankie, a fellow social change strategy agency. Galen advocates human rights and the prevention of violent conflicts through research and the judicious use of cutting edge technology. He has led research and policy projects for governments, international non-government organizations and the United Nations, alike. He’s led investigations into programmatic work, into countering violent extremism, humanitarian issues and digital rights in Southeast Asia in the Pacific, the Balkans, east Africa, and across Europe and the US.

Galen is also one of the representatives of the newly set up Extremism and Gaming Research Network. This newly established network brings together the strengths and expertise of 11 distinguished counter extremism organizations to build up the evidence base and develop concrete solutions to counter the exploitation of online gaming environments by violent extremist organizations. Galen and I have a really fun but rich conversation about the relationship between online gaming and the sense of community and belonging that it gives. We also talk in a lot of depth about why gaming communities in particular seem so appealing to terroristic movements. We also discuss how we use online communities to harness digital resiliency and minimize extremism.

“If you want to be a neo-Nazi, it’s a fight. If you are pro-democracy, it’s a fight. I think it’s a bit of a mistake to say that things have to always be peaceful and pro-inclusion. Allow people to take a little bit of an edge in that.”

Transcript: Conversation

KOSTA: All right, Galen. Welcome to Undesign. It’s so lovely to have any excuse to chat to you really? How are you doing?

GALEN: I’m doing pretty well. Thanks for inviting me into the studio again, Kosta. It’s great to be back with you.

KOSTA: I guess what we’re here to talk about today really centers around video games, right? Actually, I should mention you’re speaking to, as of three hours ago, an official owner of a PS5. I managed to find one.

GALEN: Congratulations.

KOSTA: I’m pretty excited. Do you have any gaming consoles with you where you are?

GALEN: Just my computer. It looks very plain, but it’s actually a pretty good gaming machine that I travel with.

KOSTA: If it does everything it needs to, then that’s all that matters. Again, this is probably the best segue into what we’re talking about today, which is this link between video games and extremism. There’s a flip side to it, too, but let’s start really broad. Not to … Actually, no. I’m going to very deliberately have a play on words here, which you’ll understand in a second. What would you say is the state of play with video games right now?

GALEN: I think that’s an over and overplayed pun, but I’ll take it, given that’s what we titled our last reporting.

KOSTA: Yes, I know. Yeah. What’s the lay of the land?

GALEN: It’s interesting. It’s in areas getting a lot of attention right now from a lot of governments, of NGOs, of gaming companies, gamers too. As a gamer and as a researcher of extremism and terrorism, it’s an area that has really interested me for a while. Over the last year, we’ve really dug in to see, what do we know?

Basically, the long and the short of it is there’s a lot of unanswered questions, but we see that games and gaming related spaces, things like forums, chat rooms, Discord servers, in-game chats are being used to some extent by violent extremists organizations. Gaming’s hugely popular now. We have 2.8 billion people who are gamers across the world. It’s not niche. Everyone games now. We see that COVID led this huge surge in online gaming. It’s been a source of resilience for people, a way to decompress, de-stress, connect with friends, make new friends, but those online games are social spaces. They’re not just a single player game anymore. With that, we’ve seen use of those in-game chats by extremist groups for grooming or to recruit users. We’ve also seen the production of bespoke, customized video games by groups like Hezbollah. We’ve seen modification of games by other actors, so taking things like Counter-Strike or the Sims and creating far right or just much jihadist versions of those games.

I think it’s really important that we say up front that games are not the problem here. The issue is not the fact that games create violent people or anything like that. It’s more games and gaming related spaces are being used both for specific purposes and because some extremists just happen to like games and they use it as a social space. And then the culture references get used. There’s a pop culture appeal to games and the aesthetics around them. You’ve seen ISIS propaganda material that looks like it almost came out of Call of Duty set, but it’s made by ISIS. Then we’ve seen the gamification aspect used. That’s coming from everywhere from advertising to marketing work, to education work. They’re doing things like leader boards, points, ranking systems. But we see that being repurposed by extremist actors who are using those gamified elements to unlock achievements in their manifestos or to max out on those scores for how extreme you can be in your neo-Nazi views. So we’ve seen some really worrisome developments in that space, too.

KOSTA: Mm. As far as, given you’ve had an eye on this sort of social space for a while now, is that something that exacerbated or that was in … yeah, I guess, exacerbated or encouraged by COVID and lockdowns? Was there a spike in that sort of activity too, or was the rise in that behavior, did that rise proportionately to the amount of people that were online because of COVID? Did you see any patterns there about how those two phenomena are related?

GALEN: To be upfront, we’re still working on understanding this. One thing that we’re trying to do at the … here in the Extremism Gaming Research Network is to unpack that exact question. We know there’s been a rise in online content of all forms, during COVID. So it’s difficult for me to say if there’s causation there, if there’s actually more extremist activity happening and that’s drawing on this, or just more people are online. We’ve seen a shift in communications where, before, you might meet offline if you were part of a social group or if you were part of an extremist cell. You might meet offline, discuss and try to build comradery. But that’s had to shift online in light of social restrictions, in light of movement restrictions. So there’s an element of just this is adapting to circumstances.

Another piece is that enforcement and moderation by social media platforms has, in some cases, been affective, in English for example. There’s been pretty strong English enforcement that’s happened for Twitter, for Facebook. There’s big gaps in that still, but there … that means that some extremist content has been de-platformed, and folks look for a new place to host that. You go to a live stream site. You go to DLive instead of Facebook, or you go to Telegram, or you go to an in-game chat room, and maybe you use that as your meetup spot with people who are already part of the same group, or maybe you’re trying to use that as a platform to reach new audiences.

This kind of dissent, you saw it on DLive, which is a live streaming platform that happens to host gaming content. That’s a little bit of a fringe platform. I was watching some gaming content there and then realized, “Wow, this is kind of weird.” You start tracking far right conversations merging out of these gaming videos. Then suddenly you’re watching Fox news overlaid with more extreme right radical content that then starts to get monetized because DLive had a cryptocurrency built into it. You could then donate to those causes. You then have extreme right commentators fundraising on this platform, that they’re known for talking about gaming, but the number of clicks it takes you to get there is three. I should say that after the January 6th insurrection and the capital riots in states, Dlive took down some of these folks, but there’s still a lot of extreme content there. Then they look for new platforms instead.

To answer your question, the shift to making everything online over the last two years during the pandemic period has meant that there’s lots of content that is just taking advantage of new volume of people being in online spaces, but there are some new underlying mechanisms inside of that, things like live streaming, fundraising online, and particular audio and video chats using Discord or using video-based chats instead of traditional text forums or things like WhatsApp.

KOSTA: Yeah, I see. It takes me back to the old truism in a lot of terrorism research or just terrorism knowledge, which is just this idea that terrorism is communicative and has always taken advantage of every technological advancement that we’ve ever had, from the printing press to the internet to, now, more social forms of gaming. It seems pretty par for the course that extremist groups would be able to adapt to and take advantage of some of the new ways that they can proliferate and infiltrate spaces like this. I guess my question there, what is it about gaming communities that you think extremist groups are seizing upon or sensing as fertile ground for them to apply their wares?

GALEN: That’s a great question. I think I want to be a bit careful on how I frame my answer because gamer communities are super diverse. You’re talking about hundreds or thousands of subgroups of people. I think when we say gamers or gaming communities, we’re talking about a huge diverse range of folks.

KOSTA: We can’t flatten them. Yep.

GALEN: Yep. I do think that recruiters, as well as just folks who want to spread their ideology, are always looking for folks who need meaning in their lives. We see narratives that get pushed. We were talking about … Going back to this kind of typology that I was alluding to, so if you’re creating a new video game that’s spreading your own ideology and your own narratives in it, you’re trying to share a sense of meaning. If you’re approaching folks through chats, you’re approaching folks individually who maybe reacted to some racist comments that you’re making in the chat. You’re like, “Oh right. Let me seize on that and talk to you more.”

KOSTA: Ah, I see.

GALEN: I think you’re seeing an attempt to draw folks in for a sense of identity, a sense of belonging, and those are powerful things that could be used for good. Right?

KOSTA: Absolutely.

GALEN: But because games are strong in creating that sense of shared identity in group belonging, you can then manipulate that to other ends. I think that’s the biggest one.

Another aspect I think is under investigated is around mental health in online spaces. I think part of that is like, look, if you’re looking at digital resiliency, what can we do to use games to bolster people’s resiliency online, using those same forms of identity, belonging? The fact that games can also be an educational facilitator, you can learn a lot in the game. We got to be using that to bolster folks [inaudible 00:14:31] online or it would not. The flip side is you can manipulate it and say, “I’m going to help give you a sense of belonging here. Then I’m going to help teach you. I’m going to teach you about my ideology.” Then you can get people actively engaged in that, through the game itself, but then through the social sphere around it. Those three mechanisms I think are what make games a bit different from just a traditional website or a chat or more traditional means about reaching a propaganda.

KOSTA: I guess, maybe the question I really want to ask is, are there particular types of games that you’ve noticed, even if it’s just an instinct … not trying to commit you to any sort of research findings here yet, but is it correlated with violent video games, for example, or are we seeing these sorts of conversations happen on benign stuff like … I don’t know if people play Tetris socially on streaming platforms, but I’m thinking something along those lines, a bit more benign. Is there a correlation with violent video games, which ties into a whole other preexisting narrative around the impact that violent video games, we think, has or does not have on people? Is there any relationship between the types of games people are playing and where these extremist groups are infiltrating?

GALEN: As far as we can tell, no. The research that’s been done is largely outdated on the links between violent video games and offline action. We don’t know really the causative links between what happens online, whether that causes someone to take action offline. There’s a lot of existing radicalization research that you’ve read and know quite a lot about, of different pathways, meaning for radicalization and violent extremism, [inaudible 00:16:18] that. When it comes to type the games, you have neo-Nazi groups in Roblox, which is primarily kid-centered, alternative, a game platform. You have far right groups in Minecraft, which is an assembly game.

KOSTA: Used to play that in high school.

GALEN: Yeah. Yeah. The use there is social. It’s not about the content or the narrative.

KOSTA: Right.

GALEN: You see presence in first person shooter games as well, but what we see so far is as actually the gaming type doesn’t seem to matter that much. Now, I’ll give a caveat there.

KOSTA: Sure.

GALEN: We believe it is important to unpack extremist narratives and storylines in games when those exist.

KOSTA: Okay. Yep.

GALEN: If Hezbollah makes a first person shooter, yeah, we should absolutely look at that as a narrative, but likewise in mainstream games. Did you see Far Cry 5?

KOSTA: I was literally just about to say Far Cry 5 seems to be an example that teeters on the edges of what we’re talking about.

GALEN: Right. Here’s this game, first person shooter, established series of games, and they decide to go with a far right cult and a set of conspiracy theorists, which there’s ways that you could handle that and make it a really good storyline. But instead, they disempower the user to the gamer, where you get trapped in the cult. You can’t escape it and, spoiler alert, the world ends in a nuclear inferno at the end of this, with the cult being right. You can’t do anything about it.

KOSTA: Wow. Fun.

GALEN: Yeah.

KOSTA: Fun game.

GALEN: Great game.

KOSTA: I haven’t played Far Cry 5 for a while. I haven’t played Far Cry for a while, but holy crap, that’s … There’s something to be said about the effect that media has on how we relate to the world. I think the relationship between games and our behavior is a really vexed issue in terms of popular conversation, like there’s this association between … I think one of the first examples I can remember is Columbine, where the conversation came up around the role of video games in the trajectory of those perpetrators’ decision to commit mass murder. Not to say that there isn’t an influence, because obviously these are things that are more complex than, “Yes, there’s an influence,” or “No, there’s not an influence,” but my feeling is that the current public conversation around video games and whether it’s violence or violent extremism seems to focus on the wrong part.

GALEN: I think that’s really true.

KOSTA: Okay.

GALEN: From what research has been done, there has never been a clear link establishment between violence in video games and violence offline. That’s been, if anything, largely debunked by the research that’s been done.

KOSTA: Yeah.

GALEN: Now, the online aspect is different, but again, that’s more a question of socialization and socializing. It’s less a question of exposure to violent content or violent imagery.

KOSTA: Got it.

GALEN: Can that desensitize people to violence in society. At a philosophical level, yes. At a practical level, possibly, though that’s not fully understood. But desensitizing people to violence is very different than instigating violence.

KOSTA: Okay, great distinction.

GALEN: If we want to live in a more peaceful world, I would hope that we actually sensitize people to violence and its impact, whether that’s gendered violence, whether that’s terrorism or extremist violence. I mean sure I think that’s really important, but I think saying that violence in video games or violence in movies or media causes offline violence, I have yet to see anything that shows a clear link there, but I think it’s been-

KOSTA: There’s no real compelling case for that, is there?

GALEN: Not really. There’s other things that are concerning. That’s the narrative or the role the viewer is placed. Lots there I think that we could unpack. But again, in our work, we really want to look at multiplayer games and platforms as communication channels, as social spaces where language is applied, their financing spaces even. The behavior of younger gamers is something we ought to understand better. And that link or the correlation between online activity in video games, offline behavior, we need to unpack better. But when it comes to just the games and gamified violence, I’m unconvinced, to be honest.

KOSTA: Yeah, sure.

GALEN: I think it’s a bit overdone. It’s too easy. It’s easy-

KOSTA: It’s too easy. That’s exactly what I was about to say. It just feels a bit too simple. I think like when we were preparing for this episode with our research associate, we were chatting about some of the games we played and play. It’s like some of the games I like are very problematic and violent, and at no stage do we feel compelled to even transport that into our real life situations or really make a comment about the world based on what is being presented in there. I don’t know. Do you think that’s true for most people? Is that even something that you can say? Because I would think that most people feel that way. Or is there something there that still makes alarm bells go off saying like, “Eh, people that like violent video games are more at risk of these sorts of things,” or not?

GALEN: Again, from the research that’s been done previously, so 2000 to 2010, there’s quite a bit of research into the Columbine effect, whether that existed or not. All of that debunked it. It said there’s no established correlation between people who see violence or play violent video games and their support of violence in offline environments. I think you see that now, too. 2.8 billion gamers across the world. Of that, the ones playing first person shooter are still a lot. We’re talking millions of people. Overwhelming majority don’t then take that say, “What I played online in Call of Duty or Fortnight then translates that I should be taking that offline.” That’s not the case.

Now, are there stories or narratives or tropes that could be used from those games and get into people’s heads? Yeah, absolutely. But again, that particular link I don’t see. I think there’s deeper questions on online behavior and on video games and the ways that we socialize. I think those could be unpacked more, but that violent video game, the violence bit, I think …yeah-

KOSTA: It’s still too complex?

GALEN: It’s something that’s been dissected enough that I haven’t yet to see any compelling evidence.

KOSTA: Yeah, sure. Yeah. Again, just reflecting on pop culture influence on violence or terrorism or whatever, or just on constructs of masculinity that then make you more open to some forms of violence, if you’re that way socialized, or maybe even inclined. I’m going to say something a bit silly sounding here, but I blame characters like … If we’re going to ascribe blame to anything, I ascribe blame to characters more like James Bond, for example, or like some of those really hyper masculine archetypes that were designed, I think, originally written as satirical characters or characters that were meant to be very self-aware and very flawed and not particularly likable. Through pop culture have achieved this new status, which I think some young men do interpret, or at least see themselves in, aspirationally, and in their own weird way can probably transform some of those tropes.

That’s just a personal observation, just having worked in extremism for 10 or 11 years and worked with some … just spent time looking at how people construct their own narratives, whether it’s just on comment sections or in manifestos. That pseudo commando rogue mentality is such a key characterization. Do you think that’s where some of the easy blame comes from, that if you’re playing the role, you’re actually practicing enough before you need to not practice anymore, even if the research doesn’t necessarily bear that hypothesis?

GALEN: Yeah. I think when we talk about constructs of masculinity and particularly toxic constructs of masculinity and their depiction in pop culture, I think there’s a lot of ripe territory there to question and look into. Links between toxic masculinity in cell culture and then the progression from cells have also decided to commit violent acts, that’s an interesting area to look at. Again, to my mind, the question is not then about the depiction of violence in a video game. It’s a different research question. You’re asking, what are the norms and depictions and tropes around masculinity, and how is that performed or evidenced in a gaming environment, which is fascinating. I think there has been some work on masculinity and masculine culture games. There is a deeply misogynistic undercurrent to a lot of male gamer communities, for sure.

KOSTA: Which we saw rear its head with Gamergate, didn’t we?

GALEN: Absolutely. Absolutely. We see it with some of our female colleagues who have been doxxed or trolled for their work. So that does exist. I think, again, I would come back to questions of identity and belonging in that.

KOSTA: Yes.

GALEN: If you are insecure and if you feel listless, there’s not any real way for me to display my manhood, my masculinity, and you’re given a set of tropes to grasp onto, whether that’s James Bond, whether that’s American Sniper, those kind of pseudo commando role that usually it’s actually not born by people in the military, but people who would like to pretend that they are.

KOSTA: Yeah. Funny, though.

GALEN: You know? Yeah. The wraparound Oakleys with the army T-shirt. You’re like, “Wait, were you in the army.” They’re like, “No.” And you’re like, “Wait. Wait a second.”

KOSTA: Hang on a second.

GALEN: “What? What are you?” This is getting on a bit of a different tangent, but I think-

KOSTA: Sure, there’s so many.

GALEN: There’s absolutely a conversation to be had there around performative displays of masculinity and how those come up in online gaming and gaming affinity spaces, like 4chan or 8kun. It was rife with this. But the link that I see there is not between video games or depiction of violence in video games. It’s what are the norms and tropes and morays around masculinity that are depicted and how those get socialize and picked up.

KOSTA: Exactly. That seems to be the recurring theme here, Galen. Again, very much in line with what we know about radicalization to violent extremism, in general, is this idea of socialization. I guess, your research perspective is more such that it’s not so much the content as much as the way the social settings interact with that content.

GALEN: Definitely. To go a step further in the social settings, if we look at what we call affinity spaces, things that are related to games but they’re not actually game forums, live streaming, the other thing that you’ll know from the [inaudible 00:28:51] is that the messenger matters. If we look at live streaming gamers, so you’re talking about people who have audiences of millions. If that person is using their platform to talk about very misogynistic tropes like Gamergate … You look at PewDiePie right above this, not directly instating violence, but definitely perpetuating misogyny and misogynistic norms into his talks. Then you have a messenger who’s tapping into a gamer community. Some of them likely already hold those views, but a lot of them are probably more swayable. It’s those swayable middle that are then reached by credible messengers, telling them, “Actually, misogyny is what we should be all about. Who are these women to question us in the gaming world?” That type of toxic archetype is getting used by the messenger. Now, could you help to empower other creators and credible messengers to say instead, “Actually, this is a great conversation. Why are we excluding women from this? Women are great. This is insane”? Those voices should be amplified. That’s where I think there’s a lot of interesting room for positive interventions and resilience-building in games and game-related spaces, instead.

KOSTA: That’s a perfect segue into some of … Because the other thing I got a sense from reading, not only being familiar with your work, Galen, but also just reading some of the work that the Extremism Gaming Research Network has put out, like particularly that state of play that I made the pun about before, is this idea of hope and an untapped well of opportunity to create a pretty healthy, thriving, online game communities. Right? Can you speak to some of those opportunities that you see, maybe even some of the examples where you’ve seen this sort of community, the powers that it offers wielded in a really pro-social way?

GALEN: Sure. I’m glad to hear you touch on that, because I think it’s a really interesting [inaudible 00:31:04] space to look at. Games, when you pick up your PS5 or when I, on my computer, I use that to relax. I use it to unwind and de-stress. If the storyline is great, I get a good story out of it, too. If I’m playing a murder mystery add-on for a game [inaudible 00:31:24]-

KOSTA: I was going to say, what are you playing at the moment?

GALEN: I’m playing, yeah, Outer Worlds, space game.

KOSTA: Right. Oh, okay. I know that one. Yeah.

GALEN:

Yeah. You want to play a murder mystery add-on because the game getting a little boring. It’s like what do we do? Let’s make a murder mystery out of it. Great. Way storytelling, dystopian fut … good stuff across the board. When it comes to interventions, we could do some cool stuff in those spaces. The interventions that I’ve seen so far, we have seen pilots for using games and instructional activities, so using games to teach about mis and disinformation, about hoaxes online, how to fact check well. We’ve seen some of that. We’ve seen some around violent extremism and like how do you avoid radicalization? How do you avoid people trying to target you online?

KOSTA: Right.

GALEN: Most of those games fall into the flash-based in-browser category. Then nonprofits, usually with some government funding, producing them and then putting those out. My question of those is like, who is actually playing them? Now, when they play, it does a lot of good because you have, again, that sense of belonging. It’s a great educational facilitator, and you are … they keep people really engaged. So its recent pilot, one of our partners, Moonshot … you know pretty well, who-

KOSTA: Sure do.

GALEN: … did a bio look for this, and they went from something like 16 seconds that people would stay on this website to talk about approach stratization. Then they went to people actually playing a game for 16 minutes. That’s a huge increase, 30 seconds to 16 minutes, 32-fold increase in engagement time.

KOSTA: Oh, wow.

GALEN: That’s pretty cool. That’s promising. I think that’s just scratching the surface though, because flash-based games, when was the last time you played a flash-based game on [inaudible 00:33:27]-

KOSTA: I couldn’t even tell you what one is. Can you give me an example?

GALEN: Like-

KOSTA: What’s a well known one?

GALEN: RuneScape.

KOSTA: Oh, see. That’s a name I know very well, but I don’t think I’ve played that. Is Portal one of those?

GALEN: No, Portal-

KOSTA: Or just really sidestream, or is that more complex? Now, we’re getting really-

GALEN: Yeah. Yeah. I mean … It’s like stuff you played in … I played in elementary school or middle school, where you’d go to the web browser and you would-

KOSTA: Oh, like Carmen San Diego?

GALEN: There you go. Like Carmen San Diego.

KOSTA: Got it. Yes. Wow, really showing my age.

GALEN: Yeah. Like Oregon Trail, right?

KOSTA: Right.

GALEN: That level of-

KOSTA: Got it.

GALEN: … association, but in a web browser. You don’t have to download and install. You go to www.dot … I don’t know good viewer off the top of my head. These are an old-school approach. There are games gameified and that’s good. I think they’re promising.

KOSTA: Right.

GALEN:

But now imagine if we took that and brought it into 2022 and said, “All right, let’s actually work with a grade A blockbuster game on this. Let’s work on a cool narrative there, instead.” The US military has partnered with games to work on training. Why don’t we, instead, invest in the social side, too? Okay, what about some positive mental health interventions with games, or work on tapping narratives of social inclusion or hate speech. Let’s do that. Then let’s bring the messengers in. Let’s bring in top gamers to talk about these things, like the work that we did with Creators for Change, with YouTube, right?

KOSTA: Yes. Yep.

GALEN: Let’s happen to that same street, take prominent creators and invest with them. Have them actually discuss these real issues in language that is accessible, that’s not jargon, that feels real, that’s edgy, like, “Look, if we’re bullying people and make people feel shitty for who and what they are in our games, no, that’s not right.” Games should place where everyone can exchange and everyone can compete and play. The power of play, the power of rest should matter. Let’s leverage all that incredible interaction that’s happening in much more sophisticated games, and use portions of that to also build a bit of a save the world. Anyway, the games we’ve seen produced for this is some in Sri Lanka, Southern Indonesia, a couple in the States, in Europe.

KOSTA: Right.

GALEN: They’re promising, but I think they’re just scratching the surface for the potential there.

KOSTA: Yeah, sure. I feel like I’m seeing some parallels here now, just because you mentioned Creators for Change. Just for people listening, Creators for Change is a program for content creators on YouTube to use their platforms. It’s for those creators that want to use their platforms more pro-socially to talk about particular social issues, whether it’s fighting hate speech or promoting any sort of social cohesion or intercultural dialogue, whatever pro-social issue is of significance to that person. It’s about giving them the ability to be able to do that.

It’s interesting thinking about how that translates to gaming as well, because I’m hearing two streams, similar to that program, where you had creators that were creators because they were creating conversation platforms with their viewers. Right? It’s like blog style. It’s them talking to their viewers. It’s asking questions. It’s a day-in-the-life type of stuff, again, making people feel a very intimate connection and a getting to know someone on a very day-to-day level. Then you’ve got the other stream of creators that make creative works, as well, which always seemed to be really hard in the counter narrative space because I felt like … Again, personal observation here, it’s hard to make pro-social content without it becoming too benign. At least, that’s the feeling I got, that if people were trying to advance a social issue, they didn’t know how to do it without being very kumbaya or very, very Pollyannaish, as we call it, just a very kind of benign non-conflict kind of narrative. I think conflict narratives, in this situation, make even more sense with gaming because it taps into that competitive gamification, maybe, need or instinct that we might have as gamers.

I’m just trying to think of any examples of games that actually say something about the world in a way, but even if it’s a purely creative endeavor, some stories of games, you’re just like, “Holy crap. That is such an amazing story that says something about the world.” I think, for me, the best example I can think of just currently would probably be something like Horizon Zero Dawn, what it looks like for a world to regrow itself after some sort of devastating cataclysmic event and some of the ethical conundrums that the players have in trying to figure out how the hell they got there. Those sorts of things I think are also really missed opportunities or just huge opportunities, not missed, untapped opportunities to potentially leverage gaming as a messenger in and of itself for these sorts of pro-social messages. Have you seen any examples like that, where the games themselves are not necessarily angling to be counter narrative, but just happen to be?

GALEN: Yeah, that’s a really good point around engaging with creatives who are building beautiful, interesting things, but then you put the so pro-social angle on it and it’s like you lose the edge.

KOSTA: Yeah.

GALEN: This is me speaking to personal capacity.

KOSTA: Sure.

GALEN: I’m not a professional when I say this.

KOSTA: Sure, sure.

GALEN: It’s like if you want to win against fascism, it’s a fight. If you want to beat the far right, it’s a fight. You want to advocate for democracy. It’s a fight. If you want to beat neo-Nazis, it’s a fight. I think it’s a bit of a mistake to say that everything should just be peaceful pro-inclusion narratives. If you’re angry at someone who wants to commit terrorist acts and use these platforms to horrible ends, well, allow people to take a bit of an edge in that. Right?

KOSTA: Yes. Yeah.

GALEN: I think there’s a mistake in that, trying to only foster a very Bambi Pollyanna. Connection.

KOSTA: Yeah. I love that one.

GALEN: Yeah. A phrase came up earlier, online ideological conflict spaces.

KOSTA: Right.

GALEN: Sorry, but why we know where ideologies are clashing online?

KOSTA: Yes.

GALEN: Let’s back some pre-detection [inaudible 00:40:51] stand on it. There’s lots of people who are down with fighting fascism. Let’s back some folks in there who are good creatives as well and say, “Let’s tackle some of these difficult questions,” and give you good responses to win over people who are swayable in these online spaces. That is a narrative fight, and we should be very strategic in how we think through those questions. Just backing very kumbaya type dialogues I’m not sure is helpful. There’s a role for dialogues.

KOSTA: Absolutely.

GALEN: There’s a role for that, but when you’re in an online space, you got to be focused on winning a good narrative, winning [inaudible 00:41:31], because you’re describing a different ideology. If you can do that well, let’s do it. Let’s talk about why diverse, inclusive societies matter. Let’s beat that argument. Let’s look at where the alternatives led. I think, to get to your question of games that have done that, Mass Effect, online RPG has some really complex app tool [inaudible 00:41:58] their post in that. First person shooter Wolfenstein, one of the recent ones-

KOSTA: Right. Yes.

GALEN: The anti-Nazi plot line in that, not super complex. Could have done a lot more, but you had an inkling in there. Just as art, I believe that art is inherently political and the decision to exclude politics from art is in a decision in and of itself. I’m more a fan of Marina Abramović’s performance piece and saying, ,”Look, art is performative.” Art is a statement and is inherently political with a lowercase P. It doesn’t need to endorse a party or a stance, but art is generally political.

KOSTA: It says something about the world and it takes a position, right or wrong. Art that tries to reflect the world is adopting a position. And video games, as a form of art, are similar in that sense, except maybe the advantage here is that you’ve got players and consumers being the active agents of that story within that confines. Right? There’s maybe something to be said about video game design in and of itself that encourages people to think of how these things apply in their world that they live in. There’s just a paper that I looked up called More Than Just XP, in terms of just some of the other potential or the benefits that seem to be coming from understanding how video games can be wielded really well. It says that MMORPG … Is that massive multiplayer online role playing games?

GALEN: It is.

KOSTA: Got it. I always mess that one up. So MMORPGs provide opportunities for learning social skills, such as how to meet people, how to manage a small group, how to coordinate and cooperate with people, and how to participate in sociable interactions with them. We show this social learning is tied to three important types of social interaction that are characteristics of MMORPGs, players’ self organization, instrumental coordination and downtime sociability, which are three very specific, but very fundamental human needs and skills we have in order to coexist and create relationships with people. Right? That just was another example that stands out of like, oh, even the game type itself, even though there’s that tension between whether violent video games actually encourage violence or are they just … can they be separated from it, perhaps the skills you actually practice by playing video games, is there something to be said of how we translate those more practical things, rather than just the abstract characterizations in video games and whether we can actually apply those to our lives too? There seems to be a well of possibility, I guess, in terms of what we’re yet to understand.

GALEN: Yeah. I think there really is. I’m wary of just putting this up to governmental intervention, too. I think there is a call to action here for creatives and for game creators to say, “All right, dare to be a little different.” Dare to take a little bit of that edge and say, “Can’t we actually talk about interesting skills and conversations that can happen in a game?”

Lego, I think, is an interesting example of a company that’s not video game focused … well, they have created video games … but puts play and learning at the core of their company values. Here’s a really interesting case where the act of play can be transformative and wonderful. There’s no reason that video games can’t also take up a bit of that ethos. I think there’s an enormous amount of potential there to say, “How do we engage with the challenges of our time, of eroding social trust, of corrosive impacts on democracy, of mis and disinformation and fake” … I hate the phrase fake news, but of disinformation that is targeted and manipulated?

Those are all really interesting questions that could be brought into games as well, and in ways that can make them slightly less toxic to engage with and try and come up with new answers to them, and give players the ability to wrestle with some of these complex questions and figure out, “Okay, how do I come to terms with that?” Just as Lego recently decided to de-gender their Legos, right?

KOSTA: Mm. Yeah. I-

GALEN: And to say like … Okay, so this is an offline toy. We can play with social constructs in games, too. There’s some amazing things that can happen there. It is a risk. For sure, it’s a business risk for companies to take, but I think given the many pressing challenge we face right now in democratic societies and across the world, there’s a lot we can do. I think on the extremism front, there’s a lot of interesting questions that can be tackled through games, and more broad social questions, too. To your point about what happens after environmental devastation, how that can impact in a again, there’s so many interesting prospects there. Tapping into the online community side of that, we can also spur more interesting conversations in those online spaces, too. That’s not a role just for governments or for nonprofits. There’s a role for creators, individuals, to take there and say, “How do I carry forward these conversations?” When I see a really interesting game and engage with that, I’ll play it. There’s lots of indie game makers out there who do engage with this. I would love to see more of that on the blockbuster side of this, too.

KOSTA: For sure. I guess, that was going to be my next question, as we start to look towards the future now. I’m curious to see what things look like from the … like the EGRN’s perspective, like the research network’s perspective. What are the next frontiers of research and work to happen in this area about, not only trying to understand the relationship between extremism and gaming, but also the flip side of how do we harness the power of video games for good? What does that look like for you guys at the moment?

GALEN: Yeah. I think a lot of it’s really nascent, to be honest. What I’d love to see us do on the research side, like I was saying, is understand games as communication platforms and communication channels, as well, to understand the social spaces there. Then when it comes to designs and positive interventions, I really think that we need to do some more work on game design. We need to do more work on the creation of interesting and compelling games themselves, but also working the social spaces around them, to have these conversations with gamers, with creatives in this space, with people who occupy positions of prominence and say like, “Look, you’re incredible messenger with the folks who listen to you. Let’s talk about this pressing issue and why it might be close to your heart,” and not to be disingenuous in that, but really to draw it out and cosset some of these conversations, whether that’s around extremism or hate speech or misinformation, or whether that’s around gender or misogyny, sexism. Let’s entice out some of these difficult dialogues, and to also look at the conversations around resilience online, mental health online.

KOSTA: Yeah, sure.

GALEN: We use games to teach. We absolutely can, but [inaudible 00:49:48] is continue to expand the work there. I’ll make a shameless plug for the network in that we’re-

KOSTA: Please.

GALEN: … a group of researchers-

KOSTA: I was hoping you would. Yeah. Go for it.

GALEN: We’re a group of researchers and organizations that enjoy the space, but we’re pro bono network so far. We’re trying to find more funding. We’re trying to find interested parties, whether that’s from platforms themselves or from creatives or from more traditional donors in the governmental foundation spaces. We’re interested and, look, we see that there’s a problem here. We also have an opportunity here. Let’s work on it together. Your listeners and the folks who are tuning in today can find out more about us at extremismandgaming.org. You can email me at info@extremismandgaming.org.

KOSTA: Awesome.

GALEN: [inaudible 00:50:41]-

KOSTA: Which organizations are involved in this kind of coalition or alliance of researchers? Who are some of the people involved? It’s an international network of you, isn’t it?

GALEN: It is, yeah. I’m really fortunate that the origins were behind this. A year ago, we realized it’s a bit of an issue, put out feelers, and some of our colleagues had an amazing response. A lot of times we have different donors or different clients. We always work together. For this one, it’s been incredibly collaborative the whole time. Working with the Royal United Services Institute out of the UK, our partners over at M&C Saatchi World Services, Moonshot, CVE, GIFCT, the Global Internet Forum to Counter Terrorism, [inaudible 00:51:22] Dialogue, ISD. Modestadt, they do deradicalization research in Germany. Sinor, the science creator out of Austria, and the Centre for Analysis of the Radical Right, in the UK with US service intention as well. And I have a UN person. We’ve got UNDP. We have several of the UN agencies that are also really interested in joining, as well. It’s a good group, honestly.

KOSTA: I guess, just to share with people that are not necessarily in the space like we are, that’s a really amazing caliber of people and organizations that are backing something like this. Seems like the possibilities and the frontiers you could push, through that, are really exciting. Yeah, I’m all for plugging those sorts of future-thinking research initiatives, because there’s so much yet to explore. That’s what I’m left feeling in this conversation with you, Galen, that video games are … they represent an evolution of technology and storytelling and play that’s very natural, but we are learning as rapidly as it’s evolving, I suppose. How long has game streaming been a thing, like really? Over what, 10, 10 years? More? 20 years?

GALEN: Even less.

KOSTA: Even less, right?

GALEN: The most basic, yeah.

KOSTA: We’re talking about something really new. If the takeaway here is that we really need to focus as much attention, if not more, on the socializing spaces that facilitate these sorts of gameplay, that there’s a lot that we have yet to learn, but there’s lots of reasons to be hopeful that this can actually be harnessed in a really powerful way.

GALEN: I think so. I think that’s a wonderful, wonderful recap, Kosta. Yeah, one that we’re really excited to keep looking at.

KOSTA: I’m happy to hear that. Again, I’m so grateful for your time. I always love chatting to you, Galen. If anyone wants to learn more about you specifically or the work that you’re up to, where can they find you?

GALEN: Folks can always find more information, like I said, the network, extremismgaming.org, or if you’re interested in just reaching out to me, you can go to englundconsulting.org or galenenglund.org.

KOSTA: Awesome. That’s great. Well, Galen, I’m going to go run and play my PS5. I’ve got some games waiting for me, but it’s been such a pleasure. I always love chatting to you, as I said before. Have the best day and we’ll connect again really soon.

GALEN: Perfect. Kosta, thanks again. Always wonderful speaking, and enjoy the PS5.

KOSTA: Thank you. All right. Cheers. Bye.

GALEN: Cheers. Bye.

KOSTA: You have been listening to Undesign, a series of conversations about the big issues that matter to all of us. Undesign is made possible by the wonderful team at DrawHistory. If you want to learn more about each guest or each topic, we have curated a suite of resources and reflections for you on our Undesign page at www.drawhistory.com. Thank you to the talented Jimmie Linville for editing and mixing our audio. Special thank you to our guest for joining us and showing us how important we all are in redesigning our world’s futures. Last, but not least, a huge thank you to you our dear listeners for joining us on this journey of discovery and hope. The future needs you. Make sure you stay on the journey with us by subscribing to Undesign on Apple, Spotify, and wherever else podcasts are available.

How can Indigenous wisdom guide how we live and work? Darcia Narvaez & Four Arrows from Professors

Available Now (Aired July 26, 2022)

Available Now (Aired July 26, 2022)

With world leaders responding to climate emergencies, and unprecedented threats such as the pandemic and global conflict, we seem to be running headlong into a future where our learnings from the past are both too slow and too small. Have we been too attentive and attached to the wrong things, are we suffering from problems of our own unenlightened making?

We speak with Four Arrows and Darcia Narvaez, who introduce us to the limitations of the dominant worldview which has propelled a world concerned with commerce and progress, often at the expense of principles closely linked to our ability to thrive and survive as human beings. They offer us an insight into how Indigenous world views can be incorporated into our ability to adjust to the challenges we face as diverse people, trying to survive and ultimately thrive in a world which demands more reflection and adaptation than ever.

What does the future of morality look like? Tim Dean from The Ethics Centre

Available Now (Aired July 12, 2022)

Available Now (Aired July 12, 2022)

In a world of rapidly evolving expectations on citizens due to COVID, environmental pressures, and the very public role playing of morality and ethics on social media, people face a dizzying space in which to set and attune their own moral compass.

Unpicking this challenge, Dr Tim Dean, Senior Philosopher at The Ethics Centre, discusses how morality and ethics came to exist for humans and what roles they play in our modern lives today. The contagious nature of outrage on social media is uncovered, providing solutions for understanding the addictively engaging nature of cancel culture and the limitations of social media in converting outrage into positive action.

Dr Tim Dean is a philosopher and an expert in the evolution of morality, specialising in ethics, critical thinking, the philosophy of science and education. He is also the author of How We Became Human and Why We Need to Change.